Towards sustainable wellbeing: a collective flourishing approach

In May 2025, an article in The Conversation reported the results of the Global Flourishing Study, a survey exploring patterns of human ‘flourishing’ among more than two hundred thousand people in 22 countries (including the UK).

The authors made clear that flourishing is “a multidimensional state of well-being that involves positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning and accomplishment” … and that it is “about your whole life being good, including the people around you and where you live. Things such as your home, your neighbourhood, your school or workplace, and your friends all matter.”

The study explored six key dimensions of flourishing:

- Happiness and life satisfaction;

- Physical and mental health;

- Meaning and purpose;

- Character and virtue;

- Close social relationships; and

- Financial and material stability.

They also investigated issues such as optimism, peace and balance in life.

Results of the survey: is the world flourishing?

The first tranche of results from the survey present a patchy picture, with people in some countries flourishing more than in others (the UK was ranked 20th of the 22 countries surveyed). The survey also showed that older people are flourishing more than younger people; people in relationships are flourishing better than others; those who frequently attend religious services are flourishing more than those who attend infrequently or not at all; those who have been, or are, engaged in employment are flourishing more than those who are not engaged; and people who had good relationships with their parents and felt safe and healthy as children were likely to score higher on the flourishing scale later in life.

The authors report surprise at their finding that richer countries are not flourishing as well as some others. While they do well on financial stability, they score lower in meaning and relationships. The authors state that “having more money doesn’t always mean people are doing better in life.”

Taking the results as a whole, the authors conclude that “people all over the world want many of the same basic things: to be happy, healthy, connected and safe.” They find that different countries reach these goals in different ways and that “there is no one-size-fits-all answer to flourishing. What it means to flourish can look different from place to place and from one person to another.”

What does collective flourishing look like?

How, then, might we consider a collective, flourishing society? The first results from the Global Flourishing Study offer us clear evidence that we need to take a pluralistic view; that the ‘collective’ cannot be a uniformity; that we need to consider different groups within different societies flourishing in different ways, and that flourishing changes over time. We cannot, therefore, impose a universal, static and context-free definition of ‘flourishing’ and to think about the ‘collective’ means we must pay due respect to the variety and dynamics of flourishing across cultures.

Flourishing is a verb, not a noun or an adjective… Indeed, in psychology, the notion of ‘the person of tomorrow’ (Rogers, C. R. (1980). A way of being. Houghton Mifflin) is based on strengthening a person’s individual flourishing, such that through collaboration, cooperation and interaction, a flourishing society might emerge.

In the context of the environment and wider sustainability, it’s worth recalling that in 2015, 195 countries signed up to the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Goals (the SDGs).

The 2030 Agenda and SDGs provide “a shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future" (UN, 2015). At the Summit for the Future in 2024, the need to accelerate progress on the goals was reiterated and a ‘Pact for the Future’ (pdf) was published. In its first action, signatories committed to “take bold, ambitious, accelerated, just and transformative actions to implement the 2030 agenda, achieve the sustainable development goals and leave no one behind.”

The Pact also included (at Annex ii) a Declaration on Future Generations, which included a number of principles, including that “The opportunity for future generations to thrive in prosperity and achieve sustainable development must be ensured…”. Among the actions set out in the Declaration, signatories agreed to the need for “leveraging science, data, statistics and strategic foresight to ensure long-term thinking and planning, and to develop and implement sustainable practices and the institutional reforms necessary to ensure evidence-based decision making, while making governance more anticipatory, adaptive and responsive to future opportunities, risks and challenges.”

In considering sustainable wellbeing and collective, societal flourishing, then, the SDGs represent a very high-level statement of what UN Member States agree provides for ‘a good life’. The Goals are to be achieved by 2030, and there is increasing evidence that the world will be hard pushed to meet the Goals by then. The debate is starting now on what will follow the SDGs: the so-called 'post-2030 agenda'. The Pact for the Future and the Declaration on Future Generations set out the key roles that science, data, statistics and strategic foresight must play in driving forward on sustainable development.

Measuring and making progress

Helpfully, in sustainability science, there is a thriving discourse around how we measure progress towards sustainable development, with multiple frameworks being proposed that seek to move us ‘beyond GDP’ as the dominant measure of ‘progress’. Frameworks such as ‘inclusive wealth’ and ‘sustainable wellbeing’ have been proposed that consider a wide range of parameters, rather than just measuring economic activity. But strengthening our capacity to measure progress towards sustainable development is not in itself going to achieve sustainability.

To do so requires action towards strengthening other capacities, such as promoting equity and devising effective governance; linking the vast array of knowledge we have about the world with action towards sustainability; and in strengthening capacities to both enhance resilience of natural and social systems in the face of shock and surprises, while also seeking to transform those systems towards more sustainable development pathways (Clark and Harley, 2020).

With the recent publication of the first tranche of results from the Global Flourishing Study, there is a wonderful opportunity to consider the notion of ‘collective flourishing’ in terms of how the dimensions of flourishing intersect and interact with notions of sustainable wellbeing, or collective, societal flourishing, and how we frame and strengthen capacities for progressing towards sustainable development emerging from sustainability science.

How is the IES helping the world to flourish?

The Institution of Environmental Sciences (the IES) is the global professional body for environmental scientists. The IES has adopted a programme of work during 2026 and 2027 to inform and influence public policy. Within that programme, the IES will be leading debate and discussion to consider the post-2030 agenda and how this might be enacted through a ‘sustainable wellbeing framework’. The Global Flourishing Study and the wider sustainability science discourse will form significant inputs to this work.

If you’re interested in this work or would like to be part of this discussion, please contact Joseph Lewis, Head of Policy at the IES (joseph@the-ies.org) or Gary Kass, Chair of the IES External Policy Advisory Committee (g.kass@imperial.ac.uk). To support the work of the IES to inform the transition towards a sustainable and flourishing society, consider joining the IES.

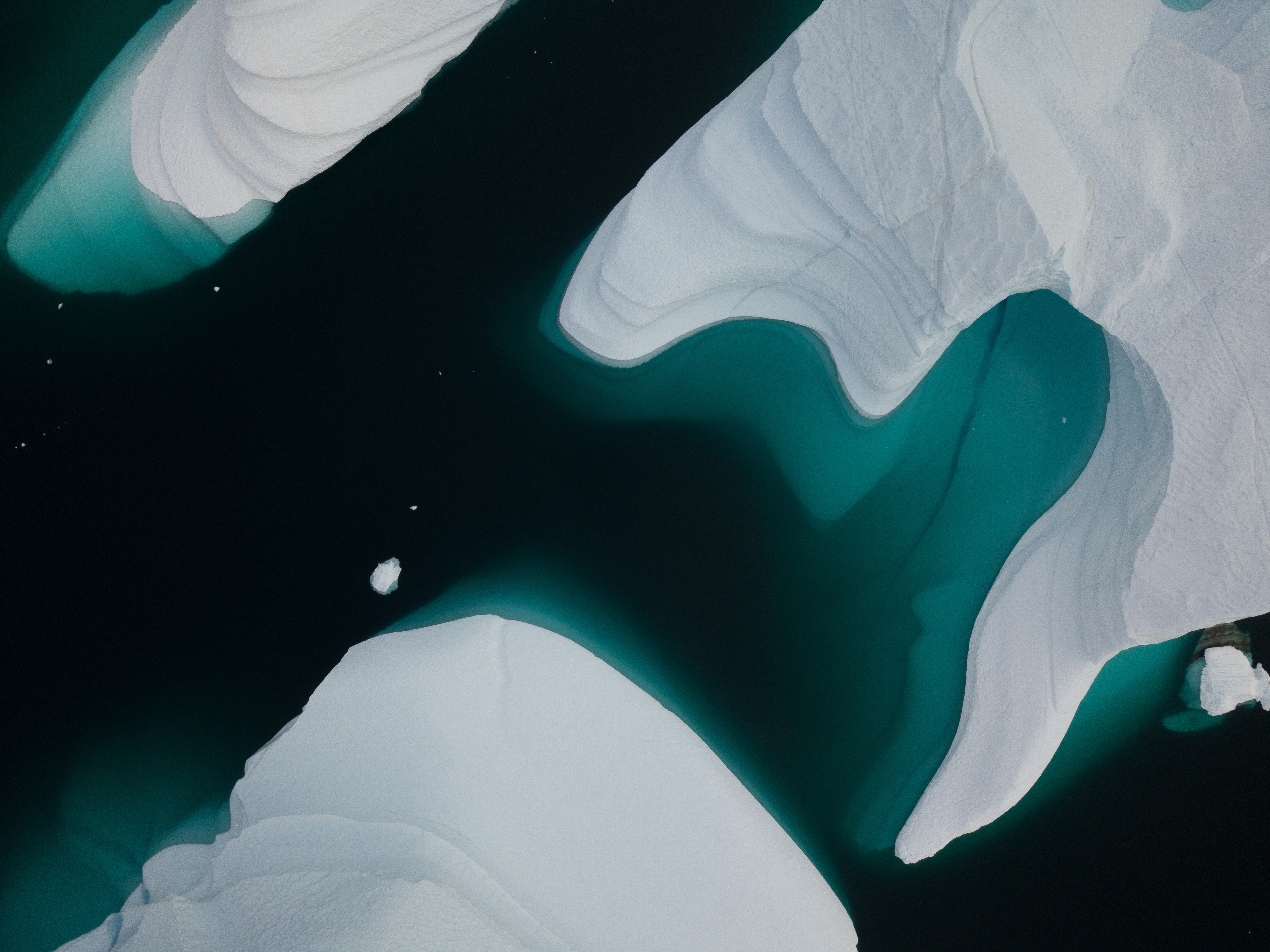

Header image credit: © schame87 via Adobe Stock