Water White Paper: An upstream glimmer of change?

In January 2026, the UK Government published its long-awaited Water White Paper. It gives a first ‘big picture’ view of the Government’s response to the Independent Water Commission and a long-term perspective on the future of water in England (and to some extent, Wales).

There are still big gaps. Many of the key delivery questions have been washed downstream to a future transition plan, which is due to come out later this year, along with further legislation. There’s now a clearer sense of the direction of travel, but big questions remain.

For now, we are recapping the key developments in the Water White Paper, mapping reactions from key stakeholders, and asking what comes next as we look ahead to what the future might hold for professionals working in the water environment.

Joseph Lewis is Head of Policy at the Institution of Environmental Sciences, working to promote the use of the environmental sciences in decision making. Joseph leads the delivery of the IES Policy Programme, standing up for the voice of science, scientists, and the natural world in policy.

Joseph Lewis is Head of Policy at the Institution of Environmental Sciences, working to promote the use of the environmental sciences in decision making. Joseph leads the delivery of the IES Policy Programme, standing up for the voice of science, scientists, and the natural world in policy.

Joseph has more than ten years of experience in public policy, including in Parliament and the charity sector. He is particularly passionate about science communication and the role it can play in shaping environmental decisions.

What do the experts say?

“The White Paper’s acceptance of the Cunliffe Review marks a significant moment for water reform, but delivery will be challenging. Regional Water Planning is a particularly promising development, especially the proposed steering group, which could help support a more joined-up approach. Given the scale of system change proposed, stronger and more explicit collaboration with the academic community would help underpin this new approach with evidence, learning, and innovation.”

- Ana Mijic, Professor of Water Systems Integration, Imperial College London

“The Water White Paper is essentially the most significant legislative change for the UK water industry since privatisation, promising a revision of key water legislation in the UK. The coming months should be a very exciting time to be an environmental professional.

However, our experience tells us that consolidating water industry plans can be very challenging. There are also some major omissions in the White Paper, including details related to human health and reducing exposure to contaminated waters, which was highlighted well by the Independent Water Commission report. It raises the question, is real reform possible within a system where the need to return profits to investors can potentially conflict with the best interests of people and planet?”

- Rebecca Wells, Consultant – Logika Group, Environmental Policy & Economics

What does the White Paper cover?

The new Water White Paper, ‘A new vision for water’, sets out a range of measures across the water environment, ranging from strategic considerations about the overall arrangement of regulators to specific operational actions around resilience and innovation funding.

- A long-term vision for water: One of the major focuses of the paper is embedding a long-term (25 year) strategic approach to water, including reform to Strategic Policy Statements, new strategic guidance to establish a clear framework for regulatory and planning discretion, an updated (and more coherent) legislative framework, an improved model for water planning through two core consolidated planning frameworks, better joined-up regional water planning, and the prospect of ambitious new water targets.

The IES and the Foundation for Water Research called for a long-term strategic approach to clean and sustainable water in 2024 as part of Our Shared Mission for Sustainable Wellbeing. The announcements in the Water White Paper are a strong step towards making that approach a reality.

The White Paper covers a wide range of other measures and proposals. A handful of the most important ones include:

- The new combined regulator: Under proposals, Ofwat will be abolished and replaced with a new regulator that takes water functions from Ofwat, the Drinking Water Inspectorate, the Environment Agency, and Natural England. The White Paper does not explicitly identify which functions (as ‘water functions’ is ambiguous in this context), but key objectives are expected to include protecting public health and the environment, strengthening financial resilience, ensuring fair and affordable bills, and providing robust oversight of infrastructure.

- Supervisory regulation: The new regulator will adopt a ‘supervisory’ approach (in line with the ‘constrained discretion’ recommendation of the Corry Review): more proactive, risk-based, company-specific, and focused on outcomes. This is expected to include new enforcement powers and the ability to act quickly against non-compliance, without needing to go to court. While the specifics will be subject to legislation, the Government has committed to addressing cultural barriers and developing decision making principles, a process to assess whether a water company can move to a new operating model, and various improvements to tools for performance management, including through contingency Special Administration Regime plans and a Performance Improvement Regime for poorly performing water companies.

- A shift towards consumers and public health: While measures here are less absolute, the Government has expressed a commitment to partnership with the Department of Health and Social Care to embed public health as a key consideration. Other proposals include a new Water Ombudsman, a drinking water quality advisory group, improved testing capability for drinking water, and a strengthened ‘customer measure of experience’.

- Innovation and investment: Another focus area for the White Paper is securing confidence for long-term investment, with a view to creating certainty and improving infrastructure. The plan commits to a blended funding approach with investment from government, investors, the regulator, and the public. The White Paper proposes a 5/10/25 year planning approach to investment, linking the 5-year cycle of price reviews with the long-term strategic vision. This will be supported by regulation to reduce risk, increase flexibility, and secure more reliable returns through a rationalised and coherent incentive framework, emulating the Government’s approach in its Carbon Budget (and Growth) Delivery Plan. Further measures include a new supplier of last resort mechanism, improved guidance for water resources planning, a consistent approach to regulation, and the expansion of Specified Infrastructure Projects Regulations to all types of water infrastructure.

- A question mark over water quality: A focus area for the White Paper is improving water quality by shifting towards ‘pre-pipe’ solutions (such as rainwater management, sustainable drainage systems, and tackling sewer misuse), with a view to prevention. The three largest sources of water pollution (agriculture, wastewater, and highway run-off) are all acknowledged in the plan, but actions are still at a level of generality, with full details expected in the forthcoming Transition Plan. The White Paper commits to ongoing partnership with the Department for Transport on road run-off, a single set of clear and strong standards for regulating agriculture, and solutions to challenges around private sewerage, but there are still questions about what those measures will mean in terms of practical implementation.

- Water in the planning system: The White Paper includes commitments around the role of water in planning, including a new plan-making system to join up water and development planning processes, a review of Permitted Development Rights for water companies in England, updated National Policy Statements for water resources and wastewater, a right to connect for water supply and to the sewerage system, and further action through the Water Delivery Taskforce.

- Emphasis on resilient infrastructure: A significant shift proposed in the White Paper is towards clearer infrastructure standards to improve asset maintenance, with embedded engineering expertise through a new Chief Engineer. This strategic shift will be backed by more funding through the Price Control process and incentives for consumers and businesses to improve water efficiency, as well as an assessment of critical supply chains and regulatory changes around abstraction and impoundment.

- Monitoring, mapping, and enforcement: After the Cunliffe Review was published, the Government made a quick commitment to end ‘operator self-monitoring’. The White Paper adds more details, including an ‘open monitoring’ approach for wastewater, improved data for Continuous Water Quality Monitoring, and a joint assessment to map infrastructure delivery needs and supply chain capability across the sector. Actions also include a set of forward-facing asset health metrics and asset mapping, with a view to supporting resilient infrastructure.

- Commitment to a transition plan… by the end of 2026: The Government has received the message from the environment sector that strategies need delivery plans. The White Paper promises a Transition Plan with a roadmap to guide the transition and assign responsibilities and deadlines. Unfortunately, the Plan itself has a very vague deadline attached, promised by the end of 2026, which leaves many of the commitments in the White Paper subject to uncertainty while we wait for key delivery information to emerge.

Many of the commitments in the White Paper are very welcome. It represents the first glimmer of a systemic approach to transforming parts of the water sector.

Yet not all that glimmers is gold, and our chance to fully grasp the reforms has been shifted downstream again.

Context: What else has happened in the last year?

The Water White Paper is the latest step in a long journey, which began with the election of a new government in 2024. Since then, the Government has made reform of the water sector one of its priorities for the environment.

In early 2025, the Water (Special Measures) Act was passed, enacting immediate reforms to water companies and addressing a handful of manifest commitments from the new Government. The more substantive question of long-term transformation of the water sector was paused, pending an inquiry from the Independent Water Commission.

From the outset, the Commission emphasised the importance of the water system to making meaningful and lasting change happen. You can find out more about the Commission’s initial call for evidence in our response to the consultation and our coverage at the time. In mid-2025, the Commission released an Interim Report, giving further details on what a systemic approach could look like. The final report of the Water Commission did not go quite as far but set out a broad list of recommendations for the Government.

Find out more about the context to these latest proposals:

- Essential Environment: A first look at the Water Commission

- Independent Water Commission: IES/FWR response to the call for evidence

- Interim report: Our analysis on a systemic approach

- Water Commission Final Report: What next?

What next?

The White Paper is a significant development. It sets the stage for meaningful reform in several parts of the water system. Some of the commitments could make a big difference, depending on how they are delivered.

This will not be a trivial implementation process. The White Paper takes on the vast majority of Cunliffe’s recommendations, so it has given itself a heavy task to complete. The process is urgent, but it will take time. It promises a shift to the regional scale, but it commits to coordination from the centre. It will be complex, but it demands coherence.

If the Transition Plan and new water targets are able to answer the question of implementation, without compromising on strong ambitions, then it may be able to move us one step closer to a system that produces better outcomes.

The next steps will be a forthcoming Green Paper from Wales, as well as the joint Transition Plan and a new Water Bill. For now, the question of detail has been washed downstream. Eventually, all things must return to the sea, so answers need to come soon.

Will these reforms deliver transformative change? Is there enough ambition hidden in the details? For now, the answers to those questions are still uncertain.

Get involved: if you want to support the work of the IES to stand up for science and nature, become an affiliate, or if you’re an environmental professional, join the IES.

- Join the Foundation for Water Research (FWR) Community to be part of our discussion on developing interdisciplinary solutions to water challenges

- Read more about these prospective reforms in the Water White Paper, as well as our analysis on the final report of the Independent Water Commission

- Learn more about recent policy developments in our briefings on clean air policy and land and nature policy

- Find out more by reading the latest articles from Essential Environment, including insights on the latest OEP progress report and our analysis on the Planning Act and what it means for environmental experts

If you want to learn more about environmental policy or the training we offer for members, please contact Joseph Lewis, Head of Policy (joseph@the-ies.org).

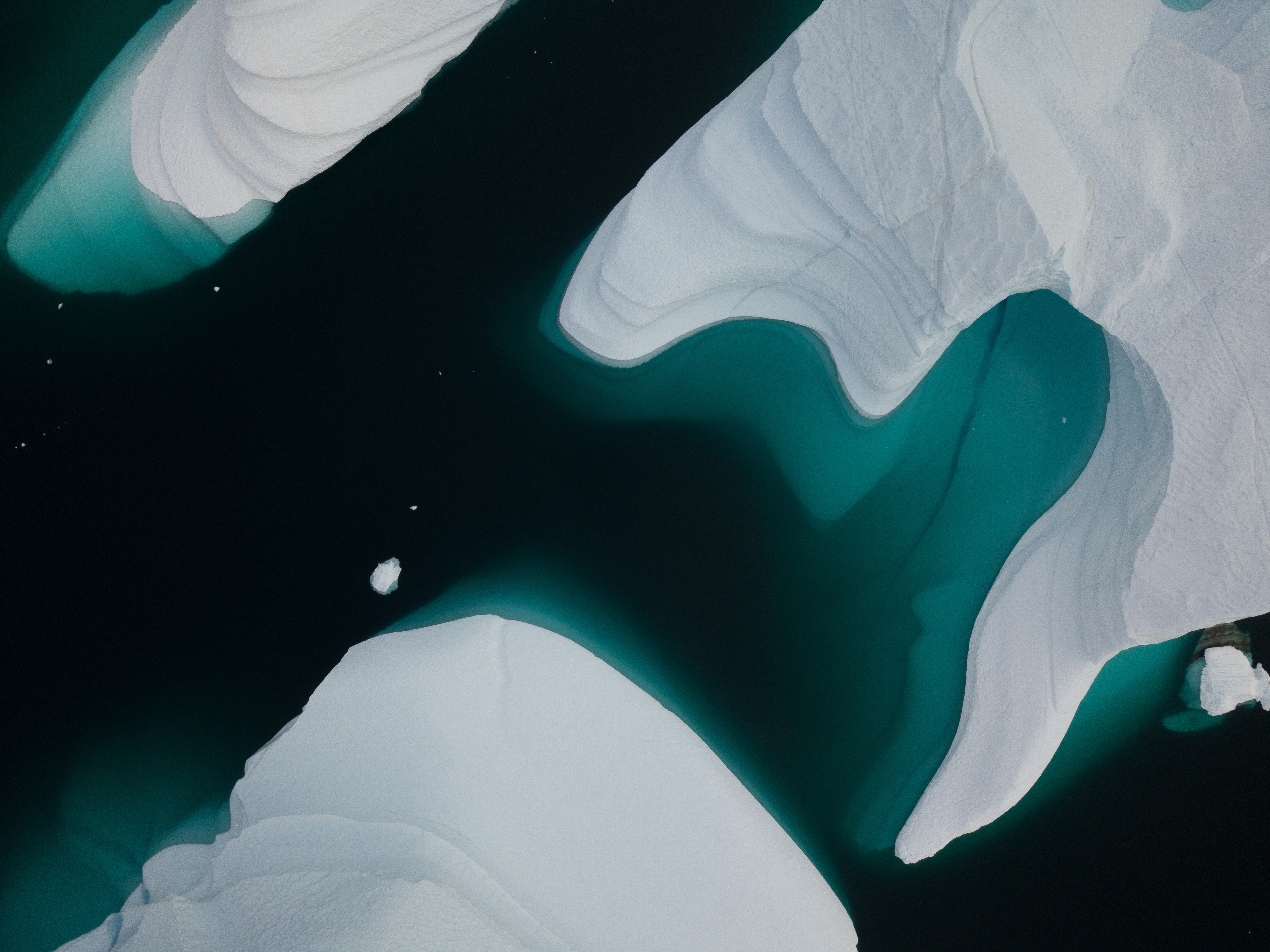

Header image credit: © Matthew via Adobe Stock