Indivisible or invisible: 10 years of the SDGs

Joseph Lewis is Head of Policy at the Institution of Environmental Sciences, working to promote the use of the environmental sciences in decision making. Joseph leads the delivery of the IES Policy Programme, standing up for the voice of science, scientists, and the natural world in policy.

Joseph has ten years of experience in public policy, including in Parliament and the charity sector. He is particularly passionate about science communication and the role it can play in shaping environmental decisions.

Ten years ago today, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted by 193 countries from all over the world, in the form of the 2030 Development Agenda.

The message was clear: a global commitment to social, economic, and environmental objectives as part of a joint and indivisible mission. 10 years on, the world’s perspective on sustainable development is beginning to appear more divided than indivisible. What went wrong?

In this anniversary article for the SDGs, IES Head of Policy Joseph Lewis discusses whether they have been successful at bringing together the constituent parts of sustainable development, whether our approach to sustainability is more divided than it was in 2015, and what it all means for the future of sustainability.

Explainer: What do the SDGs include?

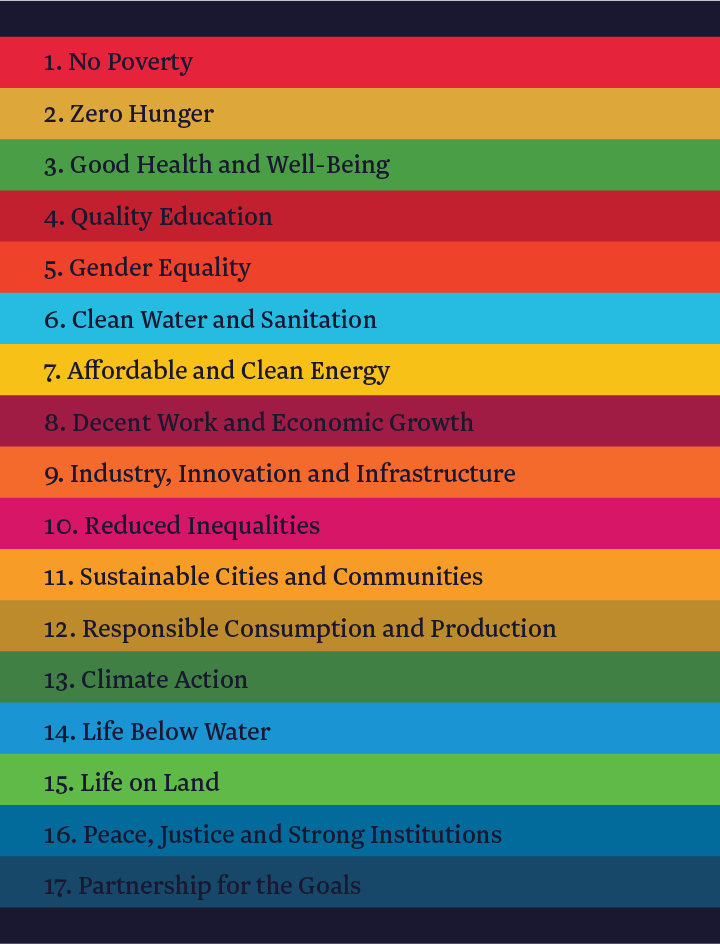

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are 17 Goals intended to create global partnership for international development that delivers social objectives like health and education, as well as environmental ones, such as tackling climate change. Surrounding the SDGs themselves is the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which is the plan that was adopted globally 10 years ago.

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals are:

|

Each of the SDGs also includes sub-targets and indicators to help measure progress towards each target. These collectively represent a detailed framework for how sustainable development could be achieved across countries and contexts.

Crucially, one key message of the SDGs was that they are “integrated and indivisible”. Put simply, not only do the choices we make about reducing poverty and fighting climate change have consequences for one another, the claim underpinning the 2030 Agenda is that it is not possible to meaningfully achieve one without the other: social, economic, and environmental objectives are part of the same shared vision.

So, have the SDGs failed?

That depends on what failure means.

Looking at the full suite of targets and indicators beneath the Sustainable Development Goals, it’s clear that many of them have not been met, though there has been a substantial degree of positive progress towards some of them.

In her recent introductory article for the environmental SCIENTIST journal on environmental indicators, IES President Julie Hill discussed the relationship between targets, indicators, and progress, noting that “without indicators forming the basis of ongoing monitoring, we will not understand to what extent we can hope to meet targets”.

In that context, even if the indicators attached to the targets beneath each SDG do not suggest that those targets have been met (or suggest that we are not making sufficient progress to meeting the goals), have they nonetheless been successful at driving action towards sustainability?

Definitions matter on paper, direction matters in practice.

When we’re dealing with difficult challenges like sustainability, we need clear targets and indicators to know if we are making progress, but they can never show the full picture. Where we are ultimately asking ‘what could the future look like, and how can we make it good for everyone’, answers don’t come easily. Even something as simple as what we want from the future is near impossible to put into words, but we all know it when we see it.

Beyond the targets, is the world better developed than it was in 2015, and are we more sustainable?

The answer to both questions is probably ‘yes, but…’

Between 2015 and 2023, the Human Development Index (which broadly speaking measure length of life, healthiness, education, and standard of living) rose from 0.731 to 0.756, and in developing countries it rose from 0.680 to 0.712. Basically, compared to 2015, the average country in terms of development today might have a life expectancy 2 or 3 years older, slightly more schooling, and an increase in gross income per person equivalent to $2000 USD per year. A small yet meaningful increase in development.

…But, progress has stalled recently, and the gap between the richest and poorest countries is growing.

Alongside the SDGs, 2015 was also the year that the Paris Agreement was negotiated, beginning an acceleration in international commitments around climate change, including the self-set Nationally Determined Contributions which now form the basis of climate action. In 2015, the world’s trajectory was to exceed 3 degrees of warming above pre-industrial levels. That number has been reduced and is now somewhere between 2.1 and 2.9 degrees.

…But, carbon emissions in 2024 were the highest they have ever been. Even as the world slows down the rate at which emissions are accelerating, they are still rising. And even when emissions stop rising, there is still a long road left until we reach a sustainable climate.

In 2022, much of the world agreed to the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, setting objectives and actions for reversing biodiversity loss. The Framework represents a major shift towards the sustainability of global ambitions for nature, putting biodiversity on the same platform that climate change has been on in the past.

…But, ambitions and actions are not the same. At COP16 in 2024, negotiations stalled about how to implement the Framework in practice, and many of the most damaging practices have not slowed down.

So have the SDGs failed? Yes, but…

In a way that is unlike anything that came before them, the SDGs have embedded the concept of sustainability and a shared vision for a sustainable future at the heart of policy making around the world.

In 2021, China published a voluntary national review on its implementation of the 2030 Agenda. 148 countries have done the same (at least twice) over the last 10 years, including Brazil, Canada, the EU, India, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and the UK.

For countries in different continents, with different ambitions, with different values, to all care enough about the SDGs to submit voluntary reviews of their implementation, shows that the SDGs have had an impact. Even despite all the differences in an increasingly divided world, they have embedded the idea of a shared vision that is fused to each country’s own vision for the future.

While the promise of driving social, economic, and environmentally sustainable development may not have been fully realised over the past 10 years, the SDGs have created real change.

Lessons to learn: Interdisciplinarity is difficult

The primary purpose of the SDGs was to support sustainable development. In that context, the framing of the integration and indivisibility of the SDGs emerged: that social progress, economic growth, and sustainability are all bound up in one another and cannot be separated.

In 2017, the environmental SCIENTIST journal, ‘Science without borders’, made the case for recognising those fundamental links better, both in science and in policy. In particular, Robert Ashcroft’s article, ‘Encouraging interdisciplinarity beyond the sciences’ argued for cross-sectoral partnerships that break down the barriers between traditional disciplines to increase our ability to deliver without division.

Globally, this has not been achieved. Across the SDGs, most initiatives have remained focused on their specific area, potentially with some observance of potential co-benefits for another Goal or risks to delivering other objectives. Action that integrates the SDGs as a whole has been limited, often leading to failure.

Naturally, we can’t solve everything, everywhere, all at once. The easiest lesson to learn from this is that interdisciplinarity is difficult. Even when you have a ready-made framework that tells people to consider a wider range of consequences, human nature and longstanding institutions are geared towards seeing problems in isolation.

10 years on from the SDGs and eight years on from the article, scaling up our successes on interdisciplinary cooperation is long overdue. We can rarely see the full picture, but when we work with others, we might get a better insight into the parts they can see that we cannot. The link between people or organisations is often a good way of seeing the link between Goals or objectives.

One of the most powerful tools to bring people together for this kind of interdisciplinary partnership is a community of practice. Linked by a common interest, challenge or profession, these communities create a dedicated environment for knowledge sharing and building links between research, policy, and practice.

At the IES, Communities are an integral part of our ecosystem, providing thought leadership for their area of focus and a forum for members to network, collaborate, and shape their sector. They also look at challenges, like our Climate Action Community, which naturally lends itself to professionals from different fields or sectors coming together to solve problems, which is exactly the kind of partnership that helps to rebuild the indivisibility of sustainable development.

More information about the IES Communities and how we are working to promoting interdisciplinary connections is available on the Communities page of the IES website.

How can we get sustainable development back on track?

Inevitably, as the world revisits the SDGs and the follow-up to the 2030 Agenda, they will face criticism.

But in the face of increasing division and criticism of international environmental goals, we cannot lose sight of the bigger picture: that for the last 10 years, the SDGs have played a unique part in uniting the world around a shared positive vision. Even as we acknowledge the ways in which the SDGs have failed, we should look ahead to how we can build on that consensus and keep working towards global sustainable development.

Between now and 2030, the IES will be working with our Communities and members to consider the perspective of environmental science on the post-2030 Agenda and the future of sustainable development. Our 2024 recommendations for the UK Government included calling for a shared mission for sustainable wellbeing, which would help make sustainability a priority.

Getting the post-2030 Agenda right will be crucial if we want sustainable development to be more than a north star, helping countries make sensible, fair, improvements that use what we already know to actually get us to a better future: a world with thriving people, a healthy economy, and a flourishing environment.

Get involved: if you want to support the work of the IES to stand up for science and sustainability, become an Affiliate, or if you’re an environmental professional, join the IES.

- Find out more about our interdisciplinary and specialist member Communities and how you can join the IES

- If you have a perspective on the Sustainable Development Goals and the post-2030 Agenda, get in touch to share your views

- Learn more about the IES Communities and how they support interdisciplinary connections and partnerships

- Read more articles from Essential Environment to stay ahead of policy developments across the environment

If you want to find out more about environmental policy or the training we offer for members, please contact Joseph Lewis, Head of Policy (joseph@the-ies.org).

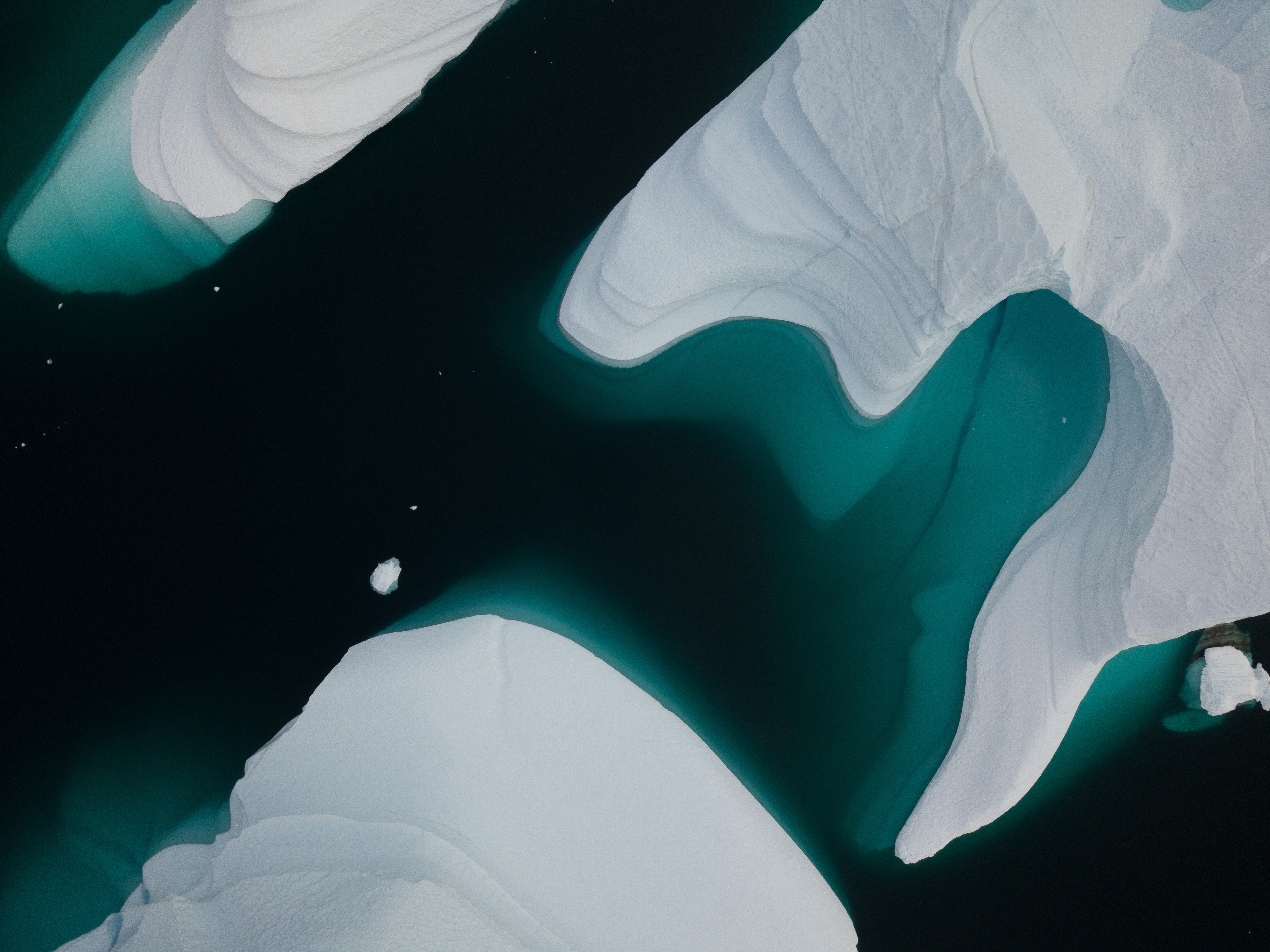

Image credit: © Renata Barbarino via Adobe Stock