environmental SCIENTIST | Animal migration | October 2021

Anna Forbes, Oli Back, Mia Ridler, Jess Mead, Joe Pecorelli and Wanda Bodnar outline the latest initiatives to improve the future of the European eel across the Thames catchment.

The European eel (Anguilla anguilla) is a fish species synonymous with the River Thames and wider Thames catchment. Tides wash young eels, known as glass eels (see Figure 1), into the Thames estuary and, in the past, they have journeyed up through the catchment rivers in large numbers. A rich cultural heritage and social history exist based on the historic abundance of this keystone species; however, this once common fish has more recently faced a steep decline.

|

| Figure 1. Glass eel. (© Jack Perks, Thames Catchment Community Eels Project) |

Eels are an unusual fish with an incredible life cycle that includes a migration of thousands of kilometres from the Sargasso Sea across the Atlantic Ocean and into our freshwater rivers – possibly the longest migration of any fish species in the world. Six organisations across the Thames catchment have partnered to work collaboratively and improve the eel’s future. The Thames Catchment Community Eels Project was developed to strategically shape future practical improvements to eel habitats – the primary focus being to address barriers to eel migration – with eel monitoring and community involvement in place to support the initiative.

The project is led by the Thames Rivers Trust which oversees project delivery of work carried out by project officers from three river trusts: Thames21, South East Rivers Trust and Action for the River Kennet. Collaboration on strategy, methodology and data analysis is also performed by the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and Thames Estuary Partnership. It is a geographically large and ambitious project, which aims to carve out a new form of partnership working as well as improve the prospects of a critically endangered species. This project is funded by the Government’s Green Recovery Challenge Fund. The fund is being delivered by the National Lottery Heritage Fund in partnership with Natural England and the Environment Agency.

About European eels

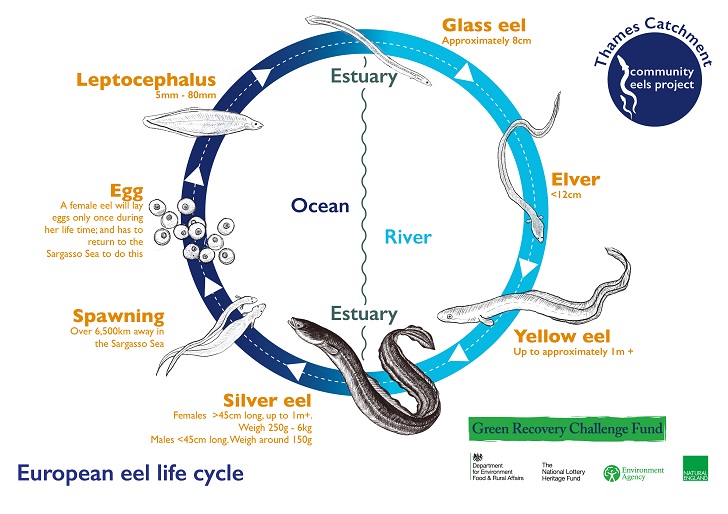

The European eel begins its life in the Sargasso Sea, over 6,000 km away from the Thames estuary. Millions of eggs laid here will hatch into eel larvae called leptocephali, often likened to a transparent leaf. These tiny leptocephali (5–80 mm long) float for approximately one to two years on the Gulf Stream before arriving on the coasts of Europe, Iceland and North Africa. Here, they metamorphose into aptly named glass eels; they are still transparent but are now a recognisable eel shape. Some will remain in the brackish waters of the estuary, but many will begin to travel up into rivers where they develop into their next life cycle stage, the elver (see Figure 2).

|

| Figure 2. Illustration of the eel life cycle. (© Thames Catchment Community Eels Project) |

Moving upstream en masse (once known as the elver run), the pigmented elvers disperse into freshwater habitats where many will spend the majority of their life, growing over many years as yellow eels. As they mature, they begin to transform into silver eels. Silver eels only reach full maturity during the six-month journey back to the Sargasso Sea; this downstream migration of the sea-bound silver eel happens in the autumn. It took hundreds of years of research to piece together the puzzle of the eel’s life, and it was not until 1920 that Johannes Schmidt discovered the probable location of where European eels spawn.1 He trawled the Atlantic Ocean over many years looking for smaller larvae until he established that their life must begin within the Sargasso Sea. Much of the eel’s life is still a mystery to scientists; no one has ever seen them mate or successfully tracked an adult eel’s return migration all the way back to where it is believed they spawn.

Why are they endangered?

The European eel has been listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List2 since 2008 due to dramatic declines in abundance recorded across all stages of its life cycle and much of its natural range. For instance, monitoring of the upstream migration shows that recruitment of young eel into the River Thames and other European rivers is only at approximately 10 per cent of what it was prior to the 1980s.

The eel’s life cycle is complex, involving both freshwater and marine phases (diadromous). As such, eels are subjected to a range of threats that include the loss of habitat in freshwater due to barriers to migration, historic drainage of wetlands, pollution, hydropower developments and unsustainable fisheries. In addition, some studies have shown that oceanic and climatic variability impact the transport of larvae and recruitment of glass eels. It is likely that, in combination, these pressures are responsible for the recent alarming decline in eel populations.

ObstacEELS: Mapping obstacles to eel migration

Weirs, sluices, locks and other man-made structures litter rivers; the Thames catchment has thousands which cause major problems for many fish species, including the eel. One of the key conservation objectives in fresh water for eel and other fish is to restore migratory pathways by removing redundant structures and adding fish and eel passes to those structures that cannot be removed. In order to do this, we first need to know where all the structures are and assess their impact on migrating fish. This is the purpose of ObstacEELS.

ObstacEELS was developed as a new citizen science project, piloted within the Thames Catchment Community Eels Project and initially targeting five rivers. For this project, the River Obstacles app, originally released in 2016, was updated to capture data specific to eels. Project officers from the three river trusts attended a one-day train-the-trainer workshop with ZSL to enable efficient training of volunteers. A volunteer Eel Force was then recruited and trained by the river trusts’ project officers. Volunteers learnt how to use the app and how to identify and classify obstacles using ZSL’s eel barrier assessment tool (EBAT), which creates a passability score. These citizen scientists were then co-ordinated by their project officer and worked in small teams to walk riverbanks and survey stretches of their local rivers, ground truthing existing datasets and logging previously unmapped barriers (see Figure 3).

|

| Figure 3. ObstacEELS volunteers and obstacles to eel migration being surveyed. (© Action for the River Kennet and Thames21) |

The pilot ran until the end of September 2021 and the results will be publicly available through the Thames Estuary Partnership’s Fish Migration Roadmap. The findings will inform the Thames River Basin District Eel Management Plan and contribute to the management plans of the catchment partnerships; it will also inform strategic plans for practical river improvement projects, such as weir removals, eel passes and eel monitoring.

Initial findings

The Thames Catchment Community Eels Project has a baseline barrier dataset consisting of barrier data from the Adaptive Management of Barriers in European Rivers (AMBER) project, Catchment Based Approach (CaBA), Environment Agency (EA) and existing data in the River Obstacles app. In addition, data from stakeholders of the relevant catchments were also gathered.

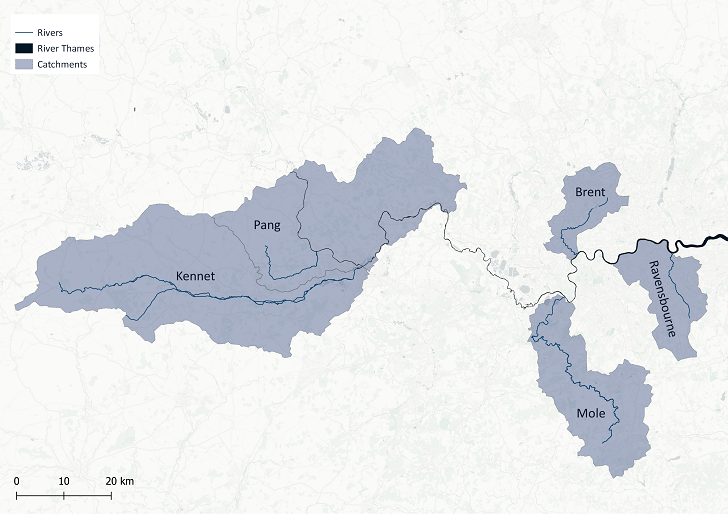

The Thames Catchment Community Eels Project has a far reach, currently running across five river catchments (see Figure 4). Full reports from each partner will be available in 2022, but initial findings are as follows:

The Kennet. The River Kennet is a chalk stream 72 km long and is the largest tributary to the River Thames. The Lower Kennet has been canalised in parts, meaning locks are the most significant barrier to eels. Often there are side streams around a lock where water flows.

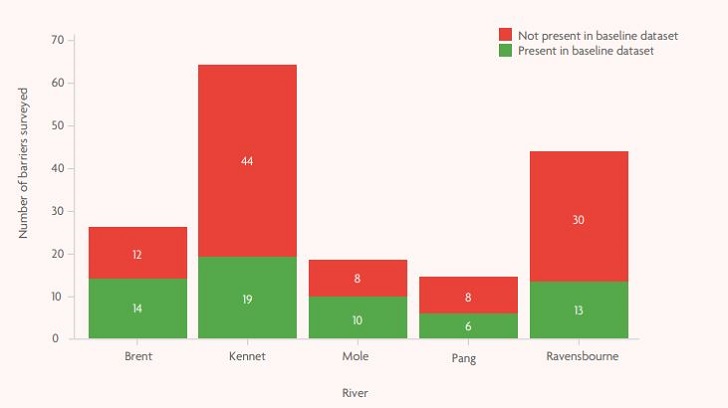

While an eel could swim around the obstacle in the side stream, some are too steep to navigate. The Lower Kennet surveys found 63 barriers, of which 44 were not recorded in the baseline dataset. This demonstrates the value of the survey, highlighting that existing data were out of date and needed ground truthing.

The Pang. The Pang is a small chalk stream river that runs for approximately 37 km from its source near the village of Compton to its confluence with the River Thames at Pangbourne. The Action for the River Kennet-trained ObstacEELS volunteers have enjoyed access to the privately owned stretches of river for barrier surveying. So far, they have identified 14 barriers, eight of which were not in the baseline dataset. When out surveying, the historic data showed nine additional barriers which volunteers observed were no longer present. These barriers were likely removed to improve fish passage.

The Mole. The River Mole is approximately 80 km long with the final 5 km forming the Lower Mole Flood Alleviation Scheme, a complex series of large barriers many of which have eel passes in place. One of these structures, Island Barn Weir, is where volunteer citizen scientists are monitoring elver numbers migrating into the catchment. Data from this season show promising numbers of eels are present, highlighting the importance of the work to record barriers and ultimately open up more habitat to eels. Upstream of here, ObstacEELS surveys are showing that previous data seem to be incomplete, with previously unrecorded barriers submitted by volunteers.

The Brent. At its confluence with the River Thames, the River Brent has a number of large locks, given the river has been completely channelised into the Grand Union Canal. These represent significant barriers to eels and have been previously assessed with some eel passes already installed. Further upstream, surveys found that much of the existing barrier data were completely out of date. During one survey it was found that there were three new barriers in place which were not listed in any datasets and one barrier had been removed but not been updated in any records.

The Ravensbourne. The majority of this catchment runs through a highly urbanised area with a population of 1.25 million people. Three rivers make up the core of this catchment: the Ravensbourne, Pool and Quaggy, and each river has been highly adapted with much of the catchments encased in concrete. Weirs were by far the dominant obstacle. In the lower half of the catchment (approximately 15 km of waterways), 100 per cent of barriers were weirs, with a total of 26 in place. Eel research has been minimal in this catchment and it is an area where eel monitoring is required.

|

| Figure 4. Map of the rivers being surveyed to inform strategic evidence-based conservation planning. (© Thames Estuary Partnership) |

The number of barriers surveyed to date (12 October 2021) compared to the baseline dataset is illustrated in Figure 5.

|

| Figure 5. Graph showing data from the five rivers targeted in this project: the number of barriers surveyed, the number of barriers present in the project’s baseline data and the number of new barriers, ‘new’ being not present in the baseline dataset. The data shown are correct as of 12 October 2021. (Source: Thames Estuary Partnership) |

Data analysis and the fish migration vision

The barrier data collected during the ObstacEELS surveys will be added to the existing Fish Migration Roadmap. The data will also be used to help the five individual catchments to develop their own catchment-specific roadmap which will include:

- Fish migratory barriers with data on fish/eel passes and EBAT;

- River connectivity data;

- River habitat data; and

- Other local data such as flood areas, development opportunity areas, land ownership etc.

The catchment-specific roadmaps will then be used to help develop a fish migration vision for each catchment. The fish migration vision is a shared long-term goal that envisions what a healthy and connected river corridor could be when there is collective action within a catchment. It relies on expert knowledge-based reprioritisation of existing barriers for the development of eel-ready proposals that will target unnecessary barriers and achieve the greatest environmental and social benefits possible. For example, a proposal involving the local council and local community may be developed to remove an impassable barrier and make a diverse habitat upstream more accessible. Activities could include educational programmes about fish and eel migration and surveying fish and eel passage (through citizen science programmes) before and after barrier removal to measure impact. Data analysis is led by the Thames Estuary Partnership which is feeding the citizen scientists’ work into an overall Fish Migration Roadmap for the River Thames.

The future

Using the data gathered during the Thames Catchment Community Eels Project, up-to-date information on river fragmentation will be visualised and shared to target improvements on the ground. Such improvements could include:

- Eel passes (see Figure 6);

- Obstacle removal;

- Habitat restoration;

- Eel monitoring; and

- Increased awareness and understanding.

|

| Figure 6. An eel pass. (© Zoological Society of London) |

Community buy-in is vital to the successful delivery of environmental projects. Increasing awareness and understanding of a species, in this case the European eel, can lead to increased value of a local river to residents, as well as support within a community for practical restoration work and involvement (e.g. volunteering and contributing ideas). The principles of connecting people with nature underpin the ethos of many of the partners on this project. The project has developed a suite of resources and is delivering a series of free community engagement activities to complement the future river improvement works.

Offerings include eel classroom and riverside workshops, eel talks and community riverbank eel walks. The walks and talks are also available to groups, clubs and organisations and are open to participants of all ages. The project partners are currently developing a partnership legacy project to expand ObstacEELS to other rivers, create new partnerships and use the new mapping data together with stakeholder engagement to carry out eel habitat improvements.

Anna Forbes is the Project Manager of the Thames Catchment Community Eels Project for Thames Rivers Trust. She has a background in leading river restoration projects, citizen science training and co-ordination, river education and community engagement.

info@thamesriverstrust.org.uk | @Thames_RvrsTrst

Oli Back is a Project Officer for Thames21. His work focuses on community engagement and improving urban rivers.

oli.back@thames21.org.uk | @thames21

Mia Ridler is a Project Officer for Action for the River Kennet, running the Thames Catchment Community Eels Project in the Kennet and Pang catchments, including ObstacEELS surveys.

mia@riverkennet.org | @ARKennet

Jess Mead is a Project Officer at the South East Rivers Trust. Her role focuses on community engagement and volunteering activities, including coordination of the trust’s citizen science initiatives. Jess is leading the ObstacEELS surveying and elver migration monitoring on the River Mole.

jess@southeastriverstrust.org @SE_Rivers_Trust

Wanda Bodnar is an Assistant Manager at the Thames Estuary Partnership. She develops, oversees and manages the Fish Migration Roadmap project. As part of the Thames Catchment Community Eels Project, she helps with barrier data management and visualisation.

w.bodnar@ucl.ac.uk | @ThamesEstPart

Joe Pecorelli is a ZSL Conservation Project Manager. In 2005, he helped set up the Thames Eel Conservation Project, which has continued to expand and develop. He now works on a broad suite of freshwater conservation projects with national impact.

Joe.Pecorelli@zsl.org | @ZSLMarine

References

- Schmidt, J. (1923) IV.—The breeding places of the eel. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character, 211 (382–390), pp. 179–208. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rstb.1923.0004 (Accessed: 17 September 2021).

- Pike, C., Crook, V. and Gollock, M. (2020) Anguilla anguilla. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T60344A152845178. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/60344/152845178 (Accessed: 17 September 2021).