In putting together his College of Commissioners, new Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker has been making some significant early changes in structure and focus. In the second post of our blog series on The end of a green Europe?, we examine the new Commission structure, and explore what these changes may mean for the environmental agenda in Europe over the coming Commission term.

Presenting his new team of Commissioners at a press conference on 10th September, Juncker announced that he had “decided to make some changes and shake things up a bit” (as reported in EUobserver). The most initially apparent of these changes is the introduction of a new Commission structure. Juncker has appointed seven Vice-Presidents in the new college, who will each be responsible for steering and coordinating the work of a number of Commissioners in teams which may change according to need and project development over time. As explained in a Commission Press Release, these project teams mirror the Political Guidelines, set out by Juncker, and on the basis of which he was elected by the European Parliament.

Juncker has also nominated a First Vice-President who will act as his ‘right-hand’. This is the first time a President has appointed a deputy in this way (in his second term Barroso enhanced the powers of the Commissioner for economic and financial affairs to effectively become his deputy) and the appointment of Frans Timmermans, who is taking on a new role focusing on ‘Better Regulaltion’, reflects Juncker’s desire to “streamline” the Commission to focus on Europe's big political challenges.

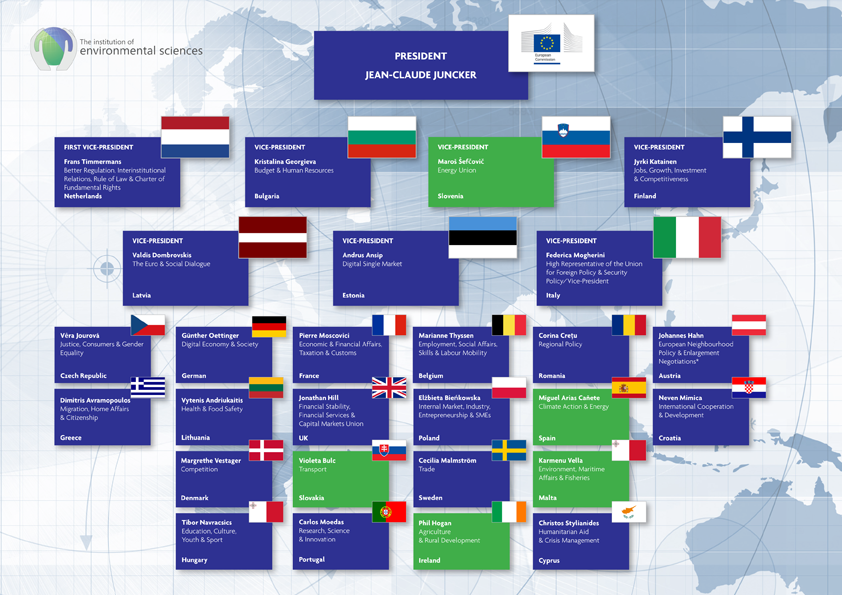

The new Commission structure is represented in the figure below. Discrete project teams cannot be easily defined, as Juncker has emphasised flexibility in the new structure, and where their portfolios fall into more than one category individual Commissioners may be answerable to more than one Vice-President.

The portfolios of those Commissioners (highlighted in green) are likely to be of relevance to various environmental professionals, as they include some elements of environmental policy. It is also worth noting however, that although the specific portfolio of the Vice-President for Jobs, Growth, Investment and Competitiveness may not be of explicit relevance to environmental professionals and scientists, his oversight of the work of the Environment, Maritime Affairs and Fisheries commissioner, and the green growth agenda, means this position is also likely to have an important impact on EU environmental policy.

Figure: Structure of the new college of Commissioners under President Jean-Claude Juncker (click for larger image)

Although keen to argue in an official press release that “there are no first or second-class Commissioners" in the new college, Juncker’s new “inner cabinet” will have a significant filtering role, as Commissioners will have to secure the support of a Vice-President in order to propose legislation. Some consider this a strength of the new structure, making the Commission more “government-like” (as argued in an article from euinside), but others have voiced concerns that the new flexible structure may actually cause confusion about who is responsible for what (as explained in an analytical article from EUobserver). It also seems that, given the shift away from environmental commitment which David Baldock of the Institute for European Environmental Policy argues the new structure and Political Guidelines seem to signal, the fortunes of the environmental agenda in the EU may depend significantly on the ability and commitment of new Commissioner responsible for the environment, Karmenu Vela, to push legislation through and win the support of Vice-Presidents.

In the new Commission structure, the portfolios for Environment and Maritime Affairs and Fisheries have been combined. The rationale for this change is to align the ‘blue’ and ‘green’ growth agendas. This could represent an opportunity to strengthen the role of the EU in protecting the marine environment. However, Juncker seems very keen to link environment conservation policies with the growth and job creation agenda; Karmenu Vela will be answerable primarily to the Vice-President for Jobs, Growth, Investment and Competitiveness, and also to the Vice-President for an Energy Union. Political commitment to green growth is to be encouraged, but the first actions of Juncker’s new Commission will be scrutinised closely over the coming months for signs that the strong environmental policy making - which the EU has been a successful vehicle and forum for in recent decades - is no longer a priority in Brussels.

The next post in this series will look in greater detail at the documents, including Political Guidelines and Mandate Letters, released by Juncker’s office so far, and what this can tell us about the priorities for his restructured Commission. The environmental sector should be watching closely to ensure its concerns are not marginalised at a time of such political change in an institution responsible for so much environmental legislation.