environmental SCIENTIST | Our common urban future | August 2015

With cities generating around 80 per cent of global GDP, there is justifiable interest in the application of smart technologies that improve transport and urban services, resource efficiency and citizen engagement. The value of the market for these technologies and associated services has been put at £260 billion by 20201 . While there is a focus on municipal and utility services, businesses are key partners in smart city strategies, as well as being agents of innovation. They too are attempting to reduce environmental impacts, enhance resource efficiency and engage with employees and external stakeholders. At the same time they have to be more transparent.

The transparency agenda

There is a growing list of demands on companies to measure and disclose information on environmental risk and performance. The regulatory picture includes the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive, the Energy Savings Opportunity Scheme (ESOS) and specific industry standards.

For listed companies in the UK, the nature of annual reporting continues to evolve with the latest iteration of the UK Corporate Governance Code and Strategic Reporting regulation, which requires greater description of material environmental and social issues. This is also a backdrop to specific demands around greenhouse gas (GHG) emission disclosure. In parallel, there is a growing movement to combine financial and other information that is relevant to company value, such as sustainability – to produce the so-called integrated report2.

While these reporting demands on larger listed companies garner all of the attention, the pressure mounts on companies of all shapes and sizes to disclose environmental and sustainability performance on an ongoing and informal basis. This may be through questionnaires from customers or criteria linked to bank lending or private equity investments.

At the same time, the technological advancements seen within the smart cities arena are changing the ways in which companies measure, analyse and disclose information on emissions, waste and resource efficiency. This is exemplified by the growth in the adoption of cloud computing, software as a service (SAAS) and access to big data generated by ground and airborne sensors (the industrial internet of things; IIoT). This in turn is challenging the nature of expectations around what a company measures, how it measures and what it discloses to different stakeholders. For example, the Digital Present report produced by the Financial Reporting Council concluded that investors prefer a timely and clear PDF version of an annual report3.

Likewise, customers, employees, communities want to know about environmental and sustainability risk on a rolling basis – when contracts are up for renewal, when seeking new suppliers or during recruitment. In parallel, environmental compliance is shifting from a monolithic test-and-approve approach to one that is more nuanced and based on risk profiling4.

While legal and customer compliance remain primary drivers for environmental measurement and management, they have been joined by the real cost pressures attached to raw materials conversion, energy and waste management. Taken together, there is real commercial pressure on companies to take a more sophisticated approach to environmental risk management. While the key technological tool deployed to achieve this goal remains the spreadsheet, there is an opportunity to turn the pain of environmental compliance into an opportunity to improve governance, enhance value and reduce costs.

Harnessing the cleanweb

Discourse on environmental and clean technologies tends to default to hardware solutions such as wind and tidal turbines, energy from waste and water treatment. Within the energy sector, there has been a flowering of smart grid and demand-management software, in line with the deploymentof smartmeters (see Figure 2).Developments in software-based data processing and analytics stem from this and is starting to change the nature of the energy supply chain.

Software-based cleanweb approaches to industrial environmentalmanagementhavebeenincreasinglyadoptedby large enterprises.The latter deploy sophisticated sustainability, environmental health and safety and carbon management software from global IT vendors or niche suppliers.

Monitoring of environmental quality on a macro scale has also been undertaken using remote-sensing technologies and geographic information systems (GIS), from satellite monitoringofforest covertoassessmentsofwaterpollution from aerial scanners. Here, there has been a focus on multinational,national andlocal government applications. However, this is changing with the rapid development and adoption of open-source mapping and geographic information (GI) software, not to mention the revolution in data collection from new satellite platforms and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Fundamentally though, not all actionable insights can be gleaned from air- and space-borne sources, so there will always be the need for data from other terrestrial sources – so-called ‘ground truth’.

Back on the ground, across great swathes of business, in particular the industrials, manual processes and the spreadsheet still hold sway. These may be sizeable companies and may have environmental managers in place, or they may be medium-sized with no formal environmental management expertise in house. What they all face are the need to control costs and satisfy the varied environmental disclosure demands of their stakeholders – regulators, customers, employees, communities, investors or lenders.

We believe that with the growing adoption and democratisation of cloud computing, data analytics, sensors and geo-spatial technologies, companies can turn the environment from compliance pain to competitive advantage.

It's all about the data... isn't it?

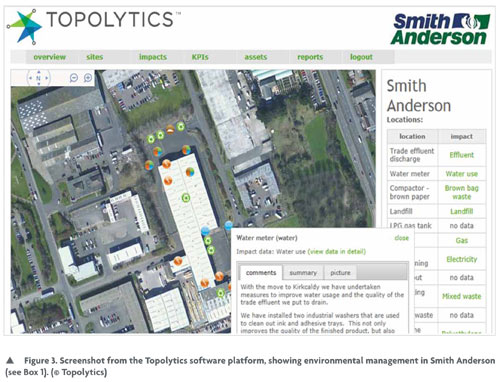

There is significant growth in commercial activity around big data and the internet of things (IoT). While consumer applications receive media attention, use of new analytical and data-collection systems is proceeding quietly across industry.Within this broader spectrum of industrial analytics and sensing, Topolytics has chosen to focus on measuring environmental risk and performance, adding context and sharing the resulting insights internally and externally.

Our core assumption is that the measurement and visualisation of environmental management is best achieved through the lens of geography.The range of data associated with environmental metrics varies widely – from manual billing through to novel sensors. However,they all operate in time and space and the latter in particular is, we believe, the glue that binds of these processes and associated data together.

Topolytics therefore takes discipline and techniques from the world of remote sensing, GIS and big-data analytics to apply them to measuring and reporting on industrial environmental risk. This allows us to work with a range of data sources, including satellite and aerial imagery, fixed and mobile sensors, automated meters, spreadsheets and manual input (see Figure 1).

Our platform is designed to allow non-expert users to incorporate a variety of data sources and add context such as narrative, documents and images in order to generate a real- or semi-real-time view of risk and performance. The data can also be exported into standard reporting formats if stakeholders require them. The business can update the system or work with their chosen advisors to maintain the data and content.

Applying geographical discipline to waste, emissions and resources can provide actionable insights and enhance transparency. Data is generated from dispersed sources in different formats, therefore the ‘geography of things’ will be a key component of the wider industrial internet of things as applied to environmental management.

From cleantech to cleanweb

Companies that operate industrial processes in or on the fringes of cities have to manage environmental risk. At the same time they can benefit from municipal adoption of smart city technologies, such as improved transport systems. Fundamentally though, these companies face the same risks of climate change as their host cities, with the added pressure to be transparent on sustainability. The rate and extent to which business adopts technology varies across the full spectrum of processes. Specifically on environmental management, the cleantech push seen over the last 10 years, exemplified by hardware solutions to energy generation, is now evolving into the cleanweb era of data, analytics and sensor-based risk management and insight.

Michael Groves is a geographer with a PhD in aerial photographic interpretation. He has a 20-year career spanning environmental management, forest certification and sustainability and is the cofounder and CEO of Topolytics, a software platform for measuring, visualising and analysing environmental risk (www.topolytics.com).

- Ove Arup & Partners ltd (2013) The Smart City Market: Opportunities for the UK. BIS research Paper No. 136. The Department for Business Innovation & Skills, London.

- International Integrated Reporting Council. Integrated reporting. www.integratedreporting.org. IIRC, London. (Accessed: 16 July 2015).

- Financial Reporting Council (2015) Lab project report: Digital present: Current use of digital media in corporate reporting. FRC, London.

- See innovation at the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency as exemplified by the Regulatory Reform (Scotland) Act 2014.